Imagine if AI just went away. Disappeared as fast as it came. No ChatGPT, Duolingo, not even that blurb at the top of the page when you look something up. A massive overhaul of the tech sector, where billion-dollar industries shatter in a night. It sounds crazy, like a B-plot in a bad movie. Believe it or not, this upheaval of the digital world might not be that far off, although much less dramatic. But that raises the question: would this be a good thing? Do AI reliance or the looming threat of model drift outweigh the benefits for the average Roosevelt student or faculty member?

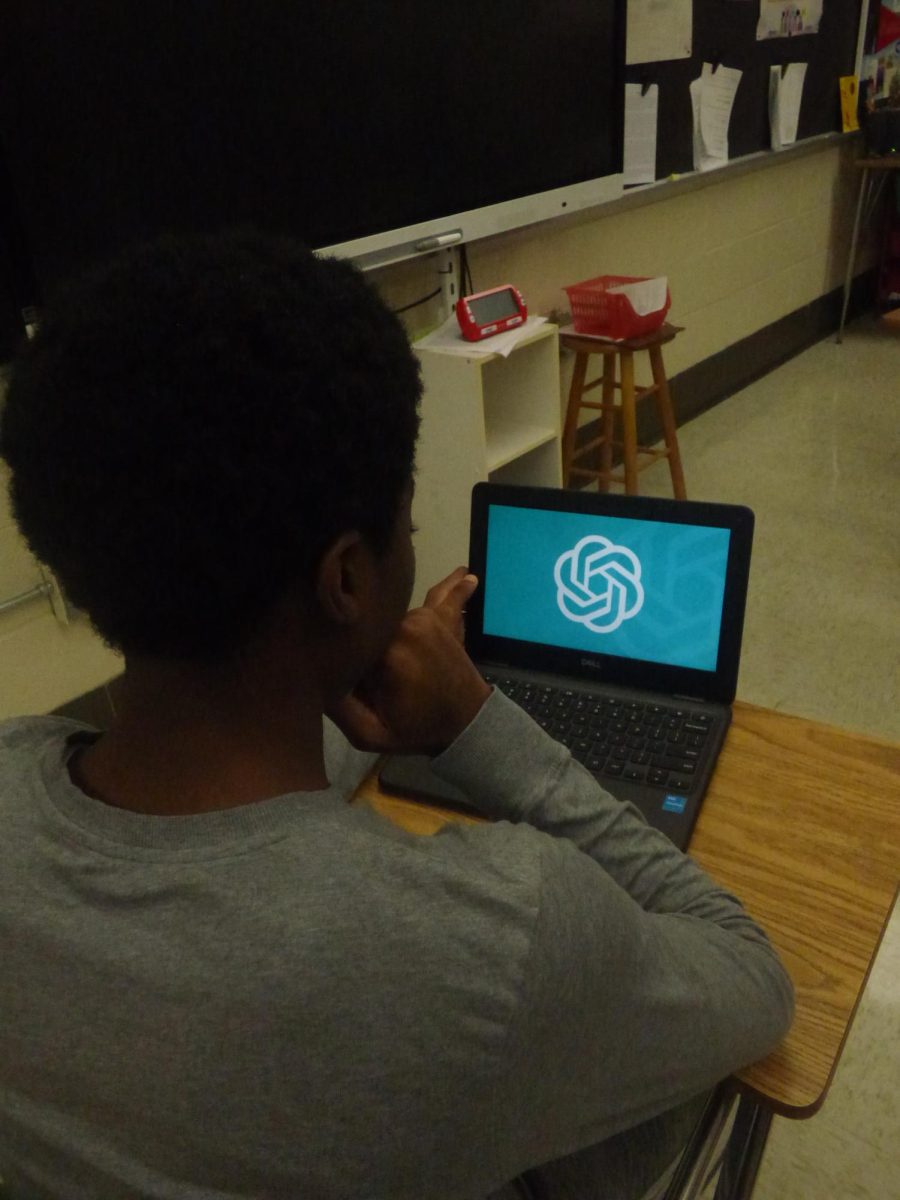

To find signs of AI dependence, a great place to start is everyone’s favorite subject: English. Yes, for some students, the introduction of AI was freedom. Freedom from the endless essays, annotations, and sleepless nights spent hunched over a poem, trying to sift through the endless purple prose to cobble together an essay due in three hours. With just a prompt and minimal editing, AI provided a break to students who desperately needed it. But this newfound freedom was not without stipulations.

Mr. James Miller, English teacher on the AP and Honors level, shares that “10% of [his] students were identified by Turnitin.com” to have been written by AI. 10% might not sound like a lot, but if we use an example of six classes with 25 students, 10% is a total of 15 students being academically dishonest for an assessment grade, every time an essay is assigned. If we lowball again at four essays assigned every year, we end up at 60 essays created with AI in a year. Keep in mind, these are charitable figures, from a single teacher, that do not take into account how many essays could have been written by AI and slipped through undetected. These stats also understate how many essays are graded by some teachers in a given year, which means the real number could be much higher if this trend continues in other subjects, like classes on the AP level.

AI doesn’t just impact our classrooms. Businesses everywhere are quickly adopting AI. Digitalsilk reporter Albert Badalyan says that “62% of companies worldwide now use AI for at least one business function”.

To further explore this, we reached out to a Roosevelt parent, Mrs. Stephanie Rizk, Chief Operating Officer of the nonprofit MDIC, or the Medical Device Innovation Consortium. The MDIC is partnered with the Center for Devices and Radiological Health and the Food and Drug Administration. As a company, they “create resources that are needed to better understand how to regulate and ensure the safety of new medical device technologies”, says Rizk. She goes on to explain how important AI is to the company, explaining how the MDIC staff uses AI to “create summaries and notes of meetings”, “draft emails and propose optional business strategies”, and “generates learning content based on our resources using an AI engine”. Rizk says that AI is a boon for productivity, that “AI has dramatically increased the speed at which we can turn around content”, and that “employing AI in our learning division decreased the time to develop learning content by over eighty percent.” Any business would benefit from that, but for a company that assists our federal regulators in keeping us safe, AI’s impact is outstanding. This is further exemplified by Rizk’s final note, that the loss of AI “would be a true cost for us”.

No article on students would be complete without the input of students themselves. We hosted a poll to gauge the opinions and habits of Raiders regarding AI. Out of the one hundred and ninety-four students who responded, about sixty-six percent technically used AI, but about fifty-one percent only used it conditionally. Eight percent of students use AI daily, and eight percent of students support the use of AI unconditionally. 35% of students denied using AI at all. By far, most polled students use AI for math-related courses, at a total of 35% of all polled students. A substantial chunk of students use AI for their English courses, at 23%. AI use in science and social studies courses are similar, at 19% and 17%, respectively. These trends express that if nothing else, ERHS students are using AI to manage their workload.

This poll also expressed that ERHS students are torn on the subject of AI. Many students shared that AI does have a place in our society, but under specific circumstances. They shared that AI could be beneficial in medical fields requiring precision, as well as diagnosing and pinpointing cancer, assisting with teaching complicated subjects, and manual tasks. Among all the responses, most students agreed that AI has a place as a tool, but not in fields like art or being the sole educator for subjects. One anonymous freshman says that “AI cannot replace the human mind”. One senior attests to AI having no place in art, that AI should only be in fields that “don’t take over creative jobs,” like artists, writers, and editors. However, this senior stated that they would “support them to use as research assistance”. At Roosevelt, even if many students use AI, most have hard boundaries with AI use.

It’s time to address the elephant in the room. Generative AI models have a catch; the way they are designed and trained leaves them susceptible to model drift, a weakness in an AI’s ability to respond to prompts, which causes it to, as social media calls it, “hallucinate”, or provide incorrect or made-up answers.

Before we can define model drift, we have to understand the types of AI. Generative AI, which consists of models and programs that are trained on data for the purpose of creating text, images, or sounds. Think ChatGPT, DeepSeek, text-to-image models, etc. These models are considered limited memory AI, which can “recall past events and outcomes and monitor specific objects or situations over time. Limited memory AI can use past and present moment data to decide on a course of action most likely to help achieve a desired outcome”, says the IBM Data and AI team, in an article posted in October, 2023. This is different from Reactive Machine AI, which IBM describes as “AI systems with no memory and are designed to perform a very specific task. Since they can’t recollect previous outcomes or decisions, they only work with presently available data”. An example of one of these AI systems would be the AI math solvers like Desmos and Symbolab.

Model drift is a very real threat for AI, and it requires constant oversight. For example, IBM details Concept Drift, when the algorithm provides incorrect answers because there is a “divergence between the input variables and the target variables”, IBM’s Jim Holdsworth, Ivan Belcic, and Cole Stryker state. In layman’s terms, it’s when the information AI has collected is different from the information in the real world. For example, IBM outlines that the sudden ChatGPT craze drove up stock prices for OpenAI, so “a forecasting model trained before those news stories were published might not predict subsequent results”. This is because ChatGPT’s prior knowledge was not trained on current trends, so its output did not have the full picture.

Covariate shift is another type of model drift that happens when “the underlying data distribution of the input data has changed”. IBM explains this one with a scenario, that if “a website is first adopted by young people, but then gains acceptance from older people, the original model based on the usage patterns of younger users might not perform as well with the older user base”. This is another disconnect that is caused by AI’s training data not having the full picture.

AI is an incredibly young technology. Both at ERHS, and in the world, AI continues to impact most aspects of our lives. Now is the time for all of us to take some time and consider the pros and cons of AI, and make an educated decision on how we participate in it.