Thank you for considering a donation! Your donation will support the student journalists of Eleanor Roosevelt High School - MD. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment, produce print editions and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Shanghai 4

September 23, 2015

It is ironic that I felt my free-est in a country devoid of personal freedoms. The safety of the streets and my ability to go where I wanted (at least, in the physical and not virtual world) gave no hint to the crimes on basic human rights that lay beneath.

So in return for the lack of rights, I got to have adventures. With my Nikon as a bracelet I roamed around Shanghai in the afternoons after my morning Mandarin lessons.

For the first week or two, the rainy season held a firm grip on the city. The summer heat that descended afterwards was not as bad as the lore I had heard. Still, on countless occasions I found the straps of my backpack drenched in sweat, and when I returned home to the apartment of my host family I would stumble to the shower in an overheated trance. I remember when I walked over 8km across the city when the temperature had crawled up the 90s, perhaps reaching into the 100s. I walked up the two and a half flights of stairs to my school, and entered. My face was as red as a drunk, sunburned German man.

So, now catering to my short-attention-spanned, sensational-craving millennial audience, (not to be demeaning, I am just the same,) here are some anecdotes and photographs, that in detail comprise some of the most shocking, strange, absurd, and different happenings of my journey.

Part I – The Scariest Thing

It wasn’t the language barrier, and it wasn’t the people who stared at the earring-ed Americana. It wasn’t the unidentifiable meat products, or even the solitude.

The scariest thing was something I brought upon myself.

Pause for a second, and think of the glossy pages and pictures of National Geographic, the epitome of photographic excellence. To the untrained eye, those pictures seem remarkable for their technical prowess – the perfect focus, the brilliant color, the depth of the wrinkles in the portraits. You don’t realize until you do it yourself, that the truly remarkable thing is the emotional connections the photographers establish in just one shot. Taking pictures of random strangers is not easy.

When you are at home in your room, it is easy to tell yourself that you will be brave. You will stick your lens in the sartorially-wrinkled face of that elderly Chinese man, snap the shot, smile, and walk away.

Funny joke.

The Chinese seem to have an easier time with that than I.

In tourist attractions, Chinese families frequently approached me and asked for a photograph, especially with their children. Most were “waidi ren” – mainlander Chinese, foreigners to the city (a Dakota potato farmer or Texan office secretary are waidi ren to a New Yorker, for instance.)

Venerators of Western facial features, entranced waidi ren would shamelessly approach me. I was hounded at Tian’an Men Square. The person who asked me first toppled a domino; I was henceforth considered tame. Families came in quick succession, asking to take a picture or selfie with me.

One little boy squatted into a ball on the ground and pressed his ears with both fingers to drown out his hearing. His mom wanted a photograph of us two, and, simply said, he did not.

Two little yellow-shirted girls photographed me like a deranged zoo animal, pushing their silver camera six inches away from my nose. The photoshoot commenced. They shot me, I shot back.

If only someone had been there to photograph the both of us.

Eventually, our anthropological dance reached a ceasefire. I returned to Mr. He, who’s Beijing-born tongue relentlessly curled his R’s, and we crawled back through Beijing’s clogged roads, chatting in Mandarin. But that’s another story.

Returning to the original topic, I continually nagged myself about my street photography phobia. I didn’t conquer it, I just tried to work in spite of it.

Located in the center of Shanghai, People’s Park, with gorgeous gardens and a modern art museum in the center, is a peculiar symbol of China itself – as my relative noted in the summer of 2012, there is something to be said when a Van Cleef and Arpels exhibit with royal jewels lands in a park for the people.

Next to a large pond with giant lily flowers stood many men, crowded to watch an ongoing card game. I walked up to them.

“Ke yi pai zhao?” Can I take a picture? They signaled yes. I raised my Nikon and took a sucky picture or two with failed lighting, and began to walk away, but my subject urged me to snap again. Between the chestnut and black paint splotches of his pastel yellow shirt sat block cartoon H’s. Chinese men sat and stood around him, their faces carrying varied degrees of emotions. The man’s two fingers were raised, and his reptilian eyes stared miles into the lens. I clicked twice again.

I look at those eyes now and I don’t know, I will never know, what was happening behind them when I clicked that shutter.

That photo remains the best I have taken in my entire life.

Part II – The People

I was looking for a present for my Dad at the fixed gear bicycle shop Factory 5 when I got a call from my host family. They wanted me to cancel my plans for that night to go to a Muslim-Chinese Uighur restaurant with friends from my language school. The place had been dubbed online as having “ghetto belly dancing” and some of the best Uighur cuisine around town, so of course, I couldn’t resist. My plans to go there had already been cancelled once because of a typhoon. Now, I couldn’t de-code where the heck my host family was trying to take me instead. Something with horses? What is “ma xi”? Life-size chess with horses and humans?

Sensing the hopes of my host family, and at some point figuring out that “ma xi” means circus, I followed the directions of my host dad. Later in the day, he sent a taxi to pick me up, which took me to an apartment complex. My host sister and a little boy were playing on electronics, and an old “a yi” – a classic all-encompassing term for “aunt,” was milling about. She gave me wontons and a big bowl of stringy dark brown pork. The pork tasted strange to my American-trained taste buds. “A yi” kept urging me to eat more, more, more. I had to decline much of the pile of meat, not only because it tasted strange, but also because it was simply too much meat, even for a carnivorous American.

After another taxi, my host sister and I finally landed in my host dad’s car at a random meeting point. We drove to Pudong, the glitzy new part of Shanghai to the east of the Huangpu River. Glorified in the foreign imagination, Pudong is most known for its exponentially-grown skyline that only a few decades ago was nothing but farmland. Now, when you imagine Shanghai you imagine Pudong. I dislike Pudong. Pudong substantiates the claims that Shanghai possesses an artistically vapid soul.

My host sister, host dad, and I walked into the tents and took our seats. The show, Cavalia, had already begun. The horses themselves underwhelmed me. I guess Chinese urbanites haven’t had the same chances as I have had for real-life encounters with large animals. Alas, not everybody’s grandparents can live on a beef farm.

Racism soon soured the show.

Clad in primitively-styled jungle shorts, seven black acrobats emerged on the set, their bare chests displaying their chiseled muscles. As the acrobatics commenced, Chinese stereotypes of blacks must have festered like Black Death. It didn’t help that the show costumed many of the white women in princess gowns.

Racism plagues Chinese society. Over there, other women constantly praised my looks. However, I got the feeling that that had largely to do with my Northern European white looks – the shape of my eyes, the color of my skin. There is a reason why Katy Perry and not Beyoncé is popular in China.

One of my Chinese teachers, who is otherwise a total darling and exceedingly gracious and kind, told me she thought black people always looked angry. I showed her a goofy, innocuous selfie of one of my African American friends, one of the happiest people I know. She didn’t like his hair, she told me, and she still thought that black guys always look angry.

I couldn’t be mad with my teacher – that would do no good anyway. (As with the picture, I tried to combat the stereotypes she had adopted.) With little to no chance of meeting black people, there were little to no chances for her opinion to be swayed. Certainly not inclined to hostility, a bit of traveling and new experiences could completely revolutionize my teacher’s beliefs.

Chinese racism against black is nothing new. According to the website The Atlanta Black Star, “Racism against Blacks may be the strongest form of prejudice in China. Chinese racism is linked to ignorance, class divisions, ethnocentrism and colorism that exists within Chinese society,” adding, “Many people in China look down upon other Chinese of darker skin, and believe the whiter skin has more beauty.” It was prevalent in the soaring advertisements of white-skinned women, and in all of those compliments that I received.

However, and this is as important as it should be obvious: not all Chinese are racist. My host father acknowledged the trend, and although I don’t remember his exact words, they were somewhere along the following lines: “The first thing that Chinese in the US say is that they don’t like racism against them, and the second thing they say is that they don’t like blacks.” My 22-year-old host brother was definitely not racist, and I wouldn’t be surprised if he represented a contingency of globalized Chinese youth who are increasingly accepting of all groups – Blacks and Japanese included.

As much racism, materialism, and neo-Confucian anti-feminism that may go down over there, it would be wrong of me to make it seem as if that dominated my impression.

What I found more in China and Shanghai, was that if you looked past the collective unit of humans and down to the individual level, all the recognizable traits of human kindness emerged.

China is often portrayed to Americans as some gargantuan, communist, economic powerhouse full of abused factory workers and corrupt communist party officials. The subways are packed, as you might have heard, and the condensed city populations make way for horrendous pollution and overcrowding. People are looked upon as a collective unit, never examined as individuals, and that’s where we’ve gone wrong. It’s our governments that don’t get along, not us.

I was in a cab in Hangzhou when I started talking to the cab driver, who asked me my nationality. When I told him with pride that I was indeed an Americana, he didn’t respond with hostility, or anything of the like. Instead, he started talking about how much he likes American sports, and basketball, especially Kobe Bryant. I told him how to say Kobe Bryant in English, and, in an attempt to memorize it and get the pronunciation right, he said over and over again, “Kobe Blyant, Kobe Blyant, Kobe Blllyant, Bllllllyant.”

A day before that, I was walking up the stairs of my apartment building with my host dad, telling him that I don’t know how I would ever be able to thank him and his family for all that they’ve given me. His response was most interesting.

If I ever became an important person, he said, I must help improve relations between the Americans and the Chinese.

Part III – What you can get at a market – Fabric, fakes, live edible crickets, a wife

It seems that all the fun to be had at markets in the US is left to Wall Street gurus. But in China, you can get practically anything you want at one: fish, birds, flowers, insects, all types of street food, fake bags, fake sunglasses, fake scarves, fake clothes, cooking ingredients, and as of late, failing stocks.

Shanghai can market you out.

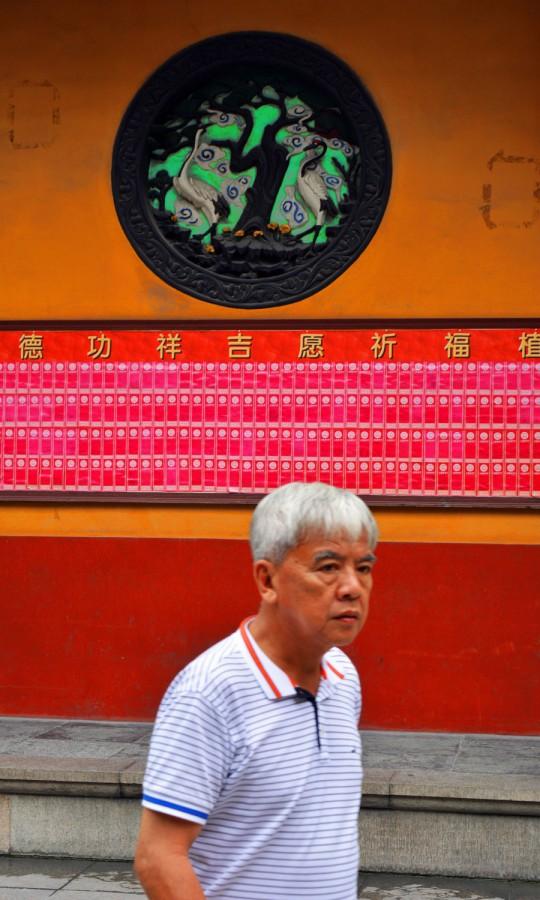

Above, are some of my pictures from the Yu Yuan Bazaar, and my favorite market, the Shanghai Marriage Market. The marriage market is a weekly gathering in People’s Park, where parents look for suitable spouses for their children. Note the sign in the second picture, which reads: “single woman seeking Caucasian man gentle female born 1986 height 1.68cm about myself educated in Australia come from an upper clans family preference single man never married.”

Part IV – Saturation

*Some of the photos in this story have been edited in color for artistic purposes.