“March: Book Two” Tells a Story of Passion and Pain

February 26, 2015

When thinking about history, one may think of school, or tests, or dusty old tomes with yellowed pages. Graphic novels might not be the first thing that comes to mind, but as March: Book Two shows, maybe it should be.

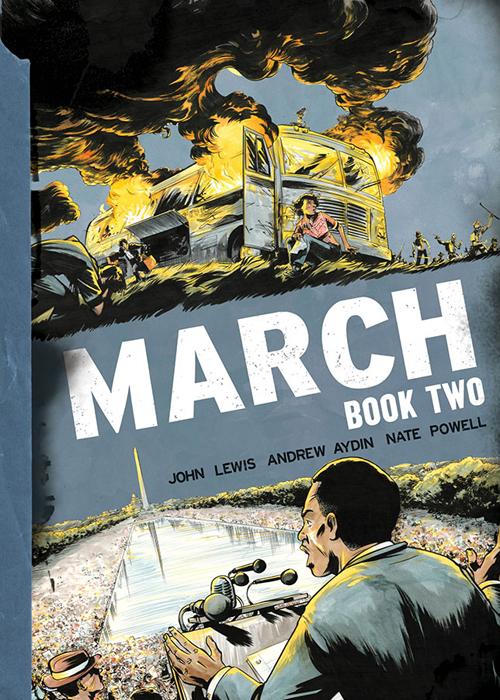

March: Book Two is the second novel in a trilogy written by Congressman John Lewis and Andrew Aydin, with art by Nate Powell. The trilogy tells the story of Lewis’s role and experiences as a leader of the Civil Rights Movement, including everything from his life as a boy in Alabama to his involvement with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). It also introduces the reader to many other leaders of the movement, such as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and James Farmer and Jim Forman.

March: Book Two focuses largely on the Freedom Rides of 1961, the protests against segregation in Birmingham, Alabama, and the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Lewis is in the thick of it all, first as a member of the Nashville Student Movement and then as a Freedom Rider and eventual chairman of SNCC, and as readers we get to follow along with his experiences.

Book One is set near the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement, but Book Two gets right to the heart of the protests, showcasing both the work done in the streets and behind the scenes. It is more violent, as well as more mature. But it is also amazing. Lewis and Aydin’s writing is straightforward and eloquent, and it gives the feeling that Lewis is telling you his story in person, sitting in front of you and recalling his life.

Lewis offers a look into the Civil Rights Movement that no textbook can provide. He shows the movement’s conflicts and discussions, from arguments over methods of protest to the orchestration of the March on Washington. And it’s fascinating. I already can’t wait to read more about the work that Lewis and his fellow leaders accomplished, because it’s a part of history that isn’t easily found in a classroom.

It’s no secret that the Civil Rights Movement was not received peacefully. While all the protests Lewis describes were nonviolent, the response—both from police and white civilians—was often not.

Powell’s art only enhances the story. It adds emphasis through depictions of angry mobs, screaming the n-word and brandishing weapons, and through depictions of armed police setting vicious dogs on protesters, then turning fire hoses on children. In providing striking black and white images that complement the words so well, Powell makes it hard to look away from the pages.

March is a difficult read. It is hard, and brutal, and tough. It cuts right into the reader and forces readers to look at, and acknowledge the awful things that the United States has done. I remember being so angry as I read some of these scenes. I’m still angry. I’m angry that this was allowed to happen, I’m angry that our country didn’t stop it. I’m angry at the millions of people who looked at the people of the Civil Rights Movement and brutally attacked them for fighting for human dignity. I’m angry that racial inequality like this still happens today, and far too often goes unchecked.

But March is not a story about hopelessness or anger. It is the story of a movement and its people, but it is also much more than that—it’s about history, and equality, and courage. It’s about determination, and fighting for what is right. It’s about love.

But most of all, it’s human. And that’s the best thing of all.